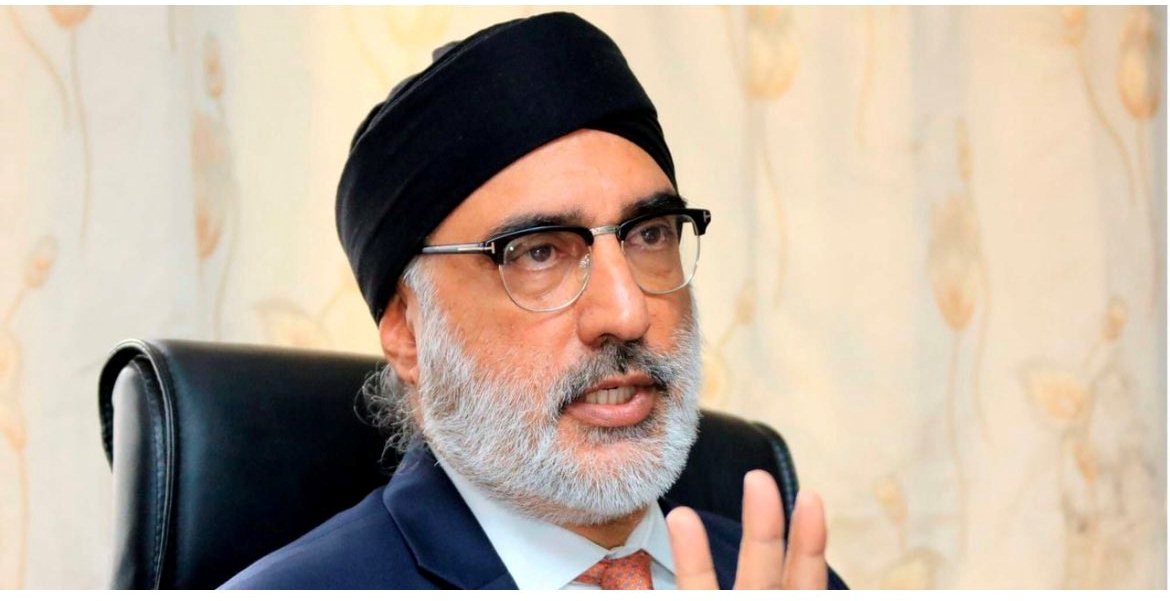

Despite repeated setbacks marked by political interventions and widespread public backlash, Jaswant Rai’s determination remains unshaken. His campaign has cast a shadow over the future of Kenya’s sugar sector and raised serious questions about the integrity of the dealings fueling this protracted saga. Rai, who owns several sugar factories in the region, including Olepito Sugar Factory in Busia County, notably bankrolled Governor Paul Otuoma’s campaign during the 2022 elections, further entangling his business interests with politics

For over five years, billionaire businessman Jaswant Rai has persistently sought to seize control of Kenya’s beleaguered Mumias Sugar Company (MSC), once a titan of the nation’s sugar industry. Despite repeated setbacks, marked by political interventions and widespread public backlash, Rai’s determination remains unshaken.

His campaign has cast a shadow over the future of Kenya’s sugar sector and raised serious questions about the integrity of the dealings fuelling this protracted saga. Rai, who owns several sugar factories in the region, including Olepito Sugar Factory in Busia County, notably bankrolled Governor Paul Otuoma’s campaign during the 2022 elections, adding a layer of political entanglement to his pursuits.

President William Ruto has repeatedly intervened to thwart Rai’s bids for MSC. The first such move followed a wave of public outrage over Rai’s ceaseless legal assaults on the company. In a moment etched into Kenyan political lore, President Ruto delivered an ultimatum with the memorable phrase, “Mambo ni Matatu,” offering Rai three stark choices: abandon the legal battles, face imprisonment, or leave Kenya entirely, with an ominous hint of “travelling to heaven.” Yet, this stern warning failed to deter Rai. His latest attempt to wrest control of MSC came shortly after Ruto’s groundbreaking decision to award sugarcane farmers bonuses, a first in Kenya’s sugar industry when Rai laid claim to MSC’s ethanol production and co-generation plants. The move triggered fierce protests, led by Kakamega County Governor Fernandes Barasa, compelling Ruto to step in once more. Summoning Rai and Tabjir Sarrai, the investor tasked with reviving MSC’s factory, to State House, Ruto ordered Rai to withdraw from Mumias Sugar immediately.

Amid this chaos, sugarcane farmers, shareholders, and industry observers ponder whether Sarrai Group, which secured the bid to resurrect MSC, can restore its past prominence. Sarrai Group’s proven track record in Uganda, where its sugar operations thrive, bolsters its credibility. It has also shown resilience at MSC, reviving sugar production despite resistance from Rai’s West Kenya Sugar Company, which has been accused of poaching MSC’s contracted farmers. However, questions remain over Sarrai Group’s handling of MSC’s ethanol and co-generation plants. While it has successfully restarted sugar production, its challenges in operationalising these facilities suggest underlying financial, logistical, or regulatory hurdles rather than outright incompetence.

Despite running multiple milling factories nationwide, Rai’s group has failed to establish its own ethanol or co-generation plants, a stark contrast to Sarai Group’s Ugandan successes. Initially, receiver manager PVR Rao permitted Rai’s group access to MSC’s facilities, but this was later rescinded, barring Rai from these lucrative assets. However, Rai’s recent claims suggest that he may still have interests in these facilities through financial manoeuvres, rather than direct operational control. This raises concerns about whether past agreements with Eco Bank and France’s Proparco, sidestepping Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB), the designated primary lender, have allowed him to retain influence over MSC’s ethanol and co-generation plants. The Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) is currently probing these transactions for possible financial irregularities, adding another layer of scrutiny.

The political backdrop grows murkier, with some leaders now advocating for a Rai-Sarrai joint venture to manage the ethanol and co-generation plants, leaders who once fiercely opposed Rai’s involvement. Their abrupt shift in position raises speculation: are they acting in the best interests of the sugar industry, or have financial and political incentives influenced their stance? If a partnership is being considered, it must be backed by transparency and an independent review to ensure it aligns with the industry’s long-term stability.

Beyond legal tussles, Rai’s group faces a grave scandal: the 2018 seizure of mercury-tainted sugar at his Pan Paper Mills in Webuye, Bungoma County. Authorities intercepted this hazardous stock, but public records detailing its official disposal remain elusive. Whether it was destroyed, resold, or remains in circulation is unclear, fuelling suspicions of regulatory lapses. Meanwhile, Rai’s acquisition of Pan Paper Mills for Ksh 900 million, against its Ksh 32.5 billion valuation, was initially celebrated as a revival effort, endorsed by then-Deputy President Ruto and retired President Uhuru Kenyatta. However, five years later, the mill remains dormant, raising doubts about Rai’s commitment to industrial growth beyond asset acquisition.

What drives Jaswant Rai? His legal battles span Mumias Sugar, Busia Sugar Industries, Butali Sugar, and Sony Sugar, hinting at an aggressive strategy to dominate Kenya’s sugar market. Yet, his group’s inconsistent record, marked by operational struggles, stalled projects, and limited financial benefits to stakeholders, casts doubt on his ability to sustainably manage these enterprises. If Rai were to regain control of MSC, would the company stagnate once more, or could his ambitions finally translate into success?

The Mumias Sugar saga endures, entangling legal disputes, political manoeuvres, and corporate intrigue. Its resolution will shape not just MSC’s fate but the trajectory of Kenya’s sugar industry. Will Rai’s relentless pursuit prevail, or will the sector finally embrace the renewal it desperately needs?