Privately, the leadership of the Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA), under Chege Kirundi, has pointed the finger at President Ruto, condemning his ‘unwise dalliance’ with the RSF as the catalyst for this crisis. Yet, in public, KTDA has remained silent, sparking murmurs of frustration from shocked farmers who question whether their new leadership lacks the courage to confront the government—or worse, is aligning itself with a regime increasingly disconnected from the struggles of the ‘hustler’ farmer

Panic has engulfed tea farmers across Kenya following the Sudanese government’s decision on 13 March 2025 to ban imports of Kenyan tea, a move that threatens to slash their eagerly awaited bonuses. The ban, a reprisal for President William Ruto’s engagement with Sudan’s rebel faction, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), has plunged the tea industry into turmoil.

Privately, the leadership of the Kenya Tea Development Agency (KTDA), under Chege Kirundi, has pointed the finger at President Ruto, condemning his “unwise dalliance” with the RSF as the catalyst for this crisis. Yet, in public, the KTDA has remained silent, drawing murmurs of frustration from shocked farmers who wonder if their new leadership lacks the courage to confront the government, or worse, is aligning itself with a regime increasingly disconnected from the struggles of the ‘hustler’ farmer.

The economic fallout is severe. Tea traders and merchants with active commercial contracts face projected losses of Ksh 6.5 to 7 billion annually. When the ban took effect, shipments destined for Port Sudan were already on the high seas, while other stocks, tailored for the Sudanese market, now sit idle in traders’ warehouses at the Port of Mombasa. Sudan, one of Kenya’s largest tea importers, has been a cornerstone of the industry, and this embargo is set to depress prices at the Mombasa auction, further eroding farmer earnings. The anticipated drop in bonuses, vital for smallholders who reaped Ksh 215.21 billion from tea exports in 2024, has heightened the sense of dread across Kenya’s tea-growing regions.

The East African Tea Trade Association (EATTA) has sounded a stark warning, reporting that over 200 containers of tea are stranded at Mombasa, with additional shipments either in transit or stalled at Port Sudan. Managing Director George Omuga noted that much of this tea was specially packaged and branded for Sudanese consumers, complicating efforts to redirect it elsewhere. He cautioned that buyers could suffer significant financial hits, losses that will reverberate back to producers and the smallholder farmers who form the industry’s backbone. The timing of the ban amplifies its sting, striking just as farmers looked forward to bonus payouts from last year’s harvest.

In a desperate bid to mitigate the damage, tea stakeholders are pressing the Kenyan government to secure a one-month grace period through diplomatic talks with Sudanese officials. This window would allow buyers to clear teas already dispatched or queued for shipment, cushioning the blow to farmers facing dwindling incomes. The plea underscores the urgent need for action to preserve Kenya’s tea market share and protect an industry critical to the nation’s economy.

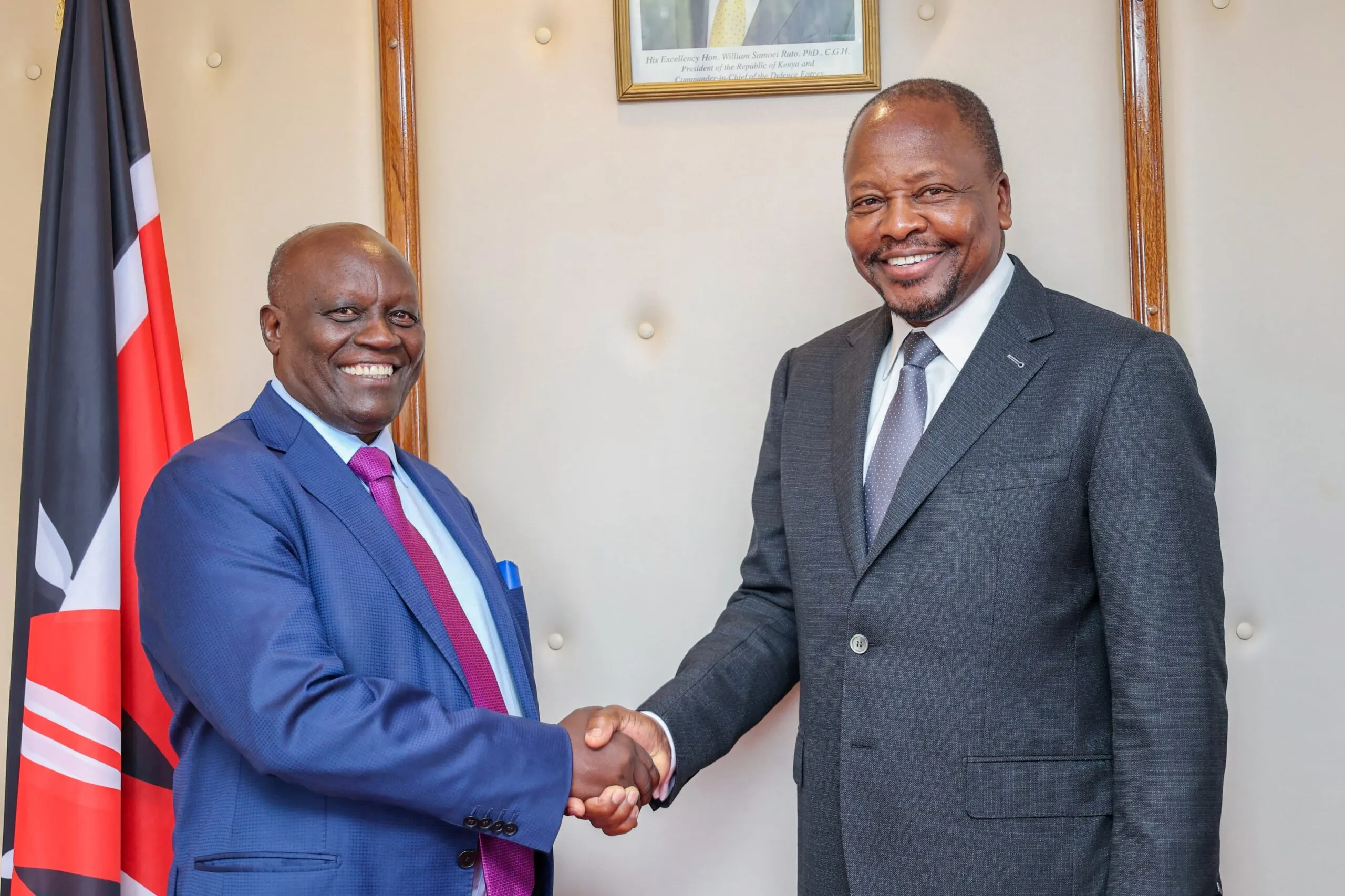

Sudan’s ban, announced by its Ministry of Trade and Supply, is a direct response to Kenya’s hosting of RSF meetings in Nairobi, which Khartoum interprets as backing for a rival faction challenging its authority. This geopolitical clash has turned tea farmers into collateral damage, exposing the fragility of Kenya’s trade ties. While Agriculture Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe stated on 13 March that diplomatic efforts were underway to resolve the market access issue, no tangible progress had emerged by 19 March 2025, leaving farmers and traders in limbo.

Publicly, the KTDA’s silence has deepened farmer unease. “We’re losing our bonuses, and they’re not even speaking up,” said a farmer from Kericho, speaking anonymously. Privately, however, KTDA insiders are outspoken, lambasting Ruto for jeopardising a key export market. This disconnect has sparked speculation: is the agency’s public reticence a calculated move to avoid conflict, or does it betray a troubling alignment with a government drifting from its pro-farmer roots? The ban’s threat to bonuses has sharpened these concerns, with farmers bracing for a lean year ahead.

The crisis lays bare Kenya’s vulnerability to regional political turbulence. Ruto’s meetings with RSF leader Mohamed Dagalo, framed as part of UN and African Union peace initiatives, have backfired, imperilling a sector that thrives on stable export markets. Without a swift resolution, the ban could flood the Mombasa auction with unsold tea, driving prices lower amid existing pressures from global trends and climate challenges. For now, Kenya’s tea heartlands remain on edge, their bonuses and livelihoods caught in the crossfire of diplomacy gone awry.