By The Weekly Vision Team

The revelation that the Kenya National Examinations Council (KNEC) has lost the title deed to a prime piece of land in Nairobi has sparked widespread public concern and raised uncomfortable questions about accountability within government institutions.

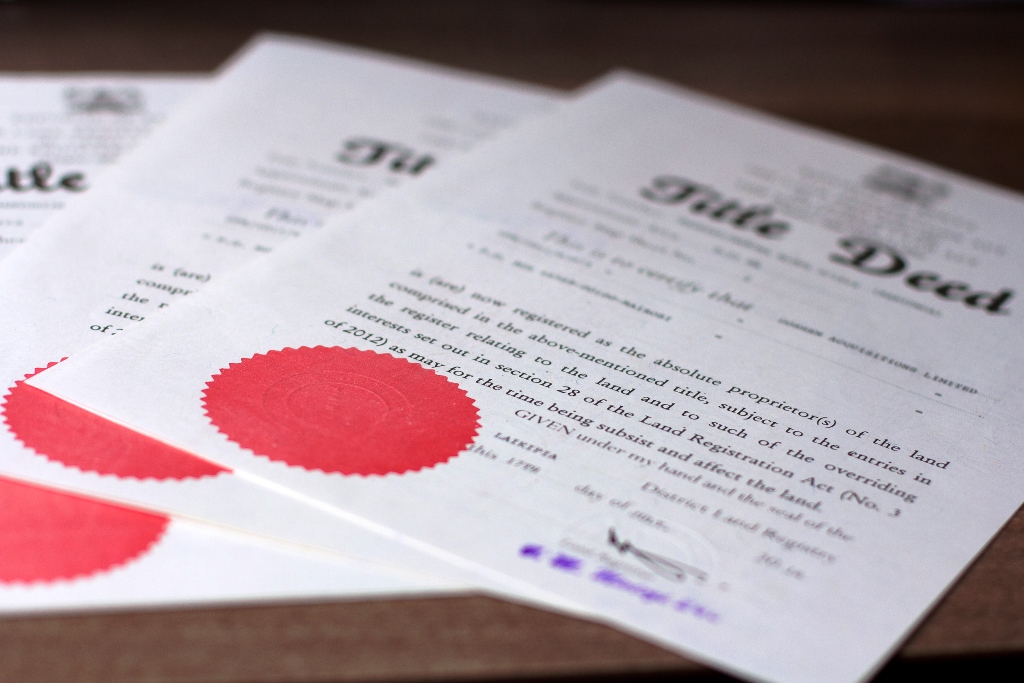

The missing title, tied to land under LR No. 209/6900, is not just any document; it is the legal cornerstone of KNEC’s claim to the property. Its disappearance, now the subject of a public appeal by the Council, lays bare the systemic weaknesses that continue to plague the custodianship of public assets.

In a notice published this week, KNEC called on any member of the public who may have come across the grant title to return it either to their headquarters in South C, to the nearest police station, or by post. The Council did not explain how the deed vanished, nor any timeline as to when it might have gone missing. This lack of transparency only compounds public disquiet.

How does a crucial government institution tasked with managing high-stakes national examinations and safeguarding sensitive data lose something as vital as a land title deed? The implications are not merely administrative; they’re potentially criminal. “This is no ordinary paperwork,” a land governance expert told The Weekly Vision. “A title deed is the most important legal proof of land ownership. Losing it suggests deep flaws in internal controls, or worse, an environment in which fraudulent interference is possible.”

Indeed, without this document, KNEC could find itself unable to defend its legal rights to the land, open to encroachment, or paralysed in its ability to undertake development projects on the property. This is not an isolated incident. A government announcement in September 2024 revealed that 366 title deeds linked to public assets are missing across various state departments. And according to the latest report by the Auditor General for the 2023/24 financial year, even critical state installations such as Harambee House and Nyayo House, which host the Office of the President and key ministries, have not provided valid land ownership documents.

Equally concerning is the finding that the National Police Service (NPS) and the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) are unable to produce title deeds for numerous government-owned properties across the country. If these lapses persist at the highest levels, what does it say about the security of smaller, less scrutinised public assets?

Beyond the embarrassment, the absence of physical or digital proof of ownership is a major liability. It complicates everything from basic maintenance to court defence in the event of disputes. It also weakens government efforts to audit, track, or invest in public properties.

Moreover, in an era of sophisticated land fraud schemes, where cartels prey on vulnerable or undocumented parcels, such carelessness is tantamount to inviting trouble. This episode should serve as a wake-up call. It’s time for government institutions to digitise land records, enforce document traceability, and establish secure archives for vital records. Internal audits must be routine and mandatory, not reactive. Heads of departments must be held personally responsible for lapses in record-keeping.

KNEC may eventually recover its missing deed. But the more pressing question is this: What else has gone missing that the public doesn’t know about yet?

Until there are clear consequences for such administrative failures, public trust in the government’s ability to manage and protect national assets will continue to erode.