By The Weekly Vision News Desk

The Nile Waters Treaty remains one of the most contentious colonial agreements still in force today. First signed in 1929 and later ratified in 1959, the treaty effectively bars upstream Nile Basin countries, including Kenya, from utilizing the waters of Lake Victoria, the source of the Nile, without Egypt’s express permission.

To unlock the full article:

Choose one of the options below:

- Ksh 10 – This article only

- Ksh 300 – Monthly subscription

- Ksh 2340 – Yearly subscription (10% off)

At the heart of the controversy lies an unjust allocation of water resources. The 1959 agreement, signed exclusively between Egypt and Sudan, allocates 66% of the Nile’s annual flow, estimated at 84 billion cubic meters, to Egypt, and 22% to Sudan. The remaining 10% is lost to evaporation and seepage. Crucially, no quota was set aside for the other riparian states: Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Eritrea.

This colonial arrangement has long been a source of resentment, particularly as population growth, climate change, and development demands place unprecedented pressure on the Nile Basin’s waters.

Since 2011, tensions have risen sharply, largely due to Ethiopia’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa’s largest hydroelectric power project. Officially commissioned this month by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, the GERD is a landmark project symbolising sovereignty and regional cooperation, particularly among the Horn of Africa nations.

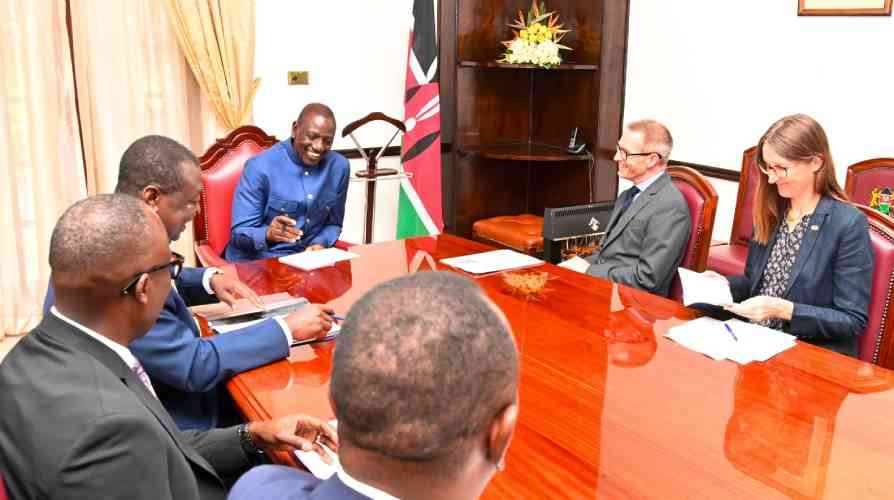

The commissioning ceremony in Ethiopia drew leaders from across the region, including President William Ruto, Djibouti’s Ismail Omar Guelleh, Somalia’s Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, and South Sudan’s Salva Kiir. International leaders, such as the Prime Minister of Barbados, also attended. Conspicuously absent, however, were Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Sudan’s Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, a stark reflection of the deep mistrust between Egypt and its upstream neighbours.

Egypt, home to more than 120 million people, depends on the Nile for over 90% of its freshwater needs. Cairo views any upstream development, especially unilateral projects like the GERD, as an existential threat. Ethiopia argues that the dam will regulate water flow and reduce flooding risks, but Egypt remains unconvinced, fearing that during droughts, Ethiopia might prioritise its own needs, worsening shortages downstream and jeopardising its fragile food security.

Egypt’s rigid insistence on the colonial-era treaty has blocked efforts to renegotiate fairer terms. Cairo treats the treaty as sacrosanct, viewing any attempt to amend it as a provocation, even tantamount to an act of war. Amid these tensions lies a pivotal yet often overlooked moment in Kenya’s diplomatic history, a moment when Kenya failed to seize its best opportunity to challenge the unfair Nile Waters Treaty and assert its rights.

In 2003, following the National Rainbow Coalition’s (NARC) rise to power, Water Minister Martha Karua was tasked with spearheading a regional initiative to contest the Nile Waters Treaty. Her goal was to unite fellow upstream states in demanding a new framework for equitable usage.

Karua’s campaign gained impressive momentum. Almost all riparian states, save for Egypt and Sudan, backed the move. It was a rare moment of solidarity and a genuine chance to overturn the entrenched status quo. Egypt, however, responded with threats of dire consequences, citing international law and hinting at military and trade retaliation. With Egypt serving as Kenya’s second-largest tea export market, its economic leverage weighed heavily on Nairobi’s calculations.

The turning point came during a high-level ministerial meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, convened to ratify initial steps toward withdrawing from the 1959 treaty. Inexplicably, Martha Karua left the meeting midway without informing either her delegation or the assembled states. To this day, she has never publicly explained her sudden exit. Whether it was due to Egyptian pressure, internal government divisions, or a broader shift in foreign policy remains a mystery.

Her abrupt departure collapsed the diplomatic momentum. Kenya did not pursue the initiative again, missing its clearest chance to lead a challenge against the colonial-era treaty. As a result, Egypt continues to dominate the Nile’s resources while upstream nations remain excluded from key decisions.

Ironically, despite ongoing tensions over water, Kenya and Egypt maintain close military ties. Both participate in defence exchange programmes, with Kenya hosting the National Defence University of Kenya (NDU-K) and Egypt offering advanced engineering training. Such defence links may partly explain Nairobi’s caution on Nile-related diplomacy.

The commissioning of the GERD could yet reignite the debate. Built over 11 years, from the era of Meles Zenawi, through Hailemariam Desalegn, to Abiy Ahmed, the dam represents more than an energy project. It is a declaration of independence for countries long subjected to inequitable water-sharing frameworks.

As upstream states press for equitable access, the Nile Waters Treaty’s future remains uncertain. What is clear is that Kenya was once primed to lead reform efforts and, by failing to act, lost that defining opportunity.

[/full]