In a stark revelation that has sent ripples through Kenya’s healthcare sector, Mosop MP Abraham Kirwa decried the quality of medicines administered in local hospitals, claiming they nearly cost him his life. Speaking candidly in parliament upon his return from extended treatment abroad, the legislator recounted a perilous health ordeal that began at the prestigious Nairobi Hospital and culminated in a desperate airlift to Dubai

To unlock the full article:

Choose one of the options below:

- Ksh 10 – This article only

- Ksh 300 – Monthly subscription

- Ksh 2340 – Yearly subscription (10% off)

By The Weekly Vision Editorial Team

A Member of Parliament has recounted how he narrowly escaped death after being administered counterfeit medicines in one of the country’s most prestigious health facilities, revealing a ticking time bomb in the country’s healthcare sector.

The MP’s shocking revelations lifted the lid on the extent to which counterfeit and substandard medicines have, inundated the Kenyan healthcare system, revealing that these fake pharmaceutical products are not confined to back-street pharmacies or informal outlets; they have infiltrated even the most prestigious and elite medical facilities across the country, including leading private hospitals and well-known chains that cater to the affluent and politically connected.

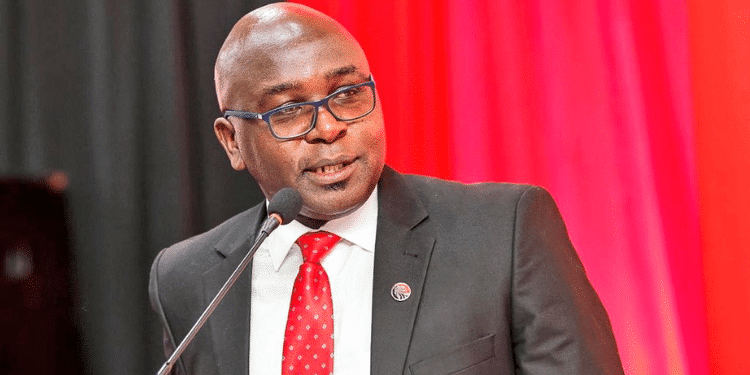

In a stark revelation that has sent ripples through Kenya’s healthcare sector, Mosop MP Abraham Kirwa decried the quality of medicines administered in local hospitals, claiming they nearly cost him his life. Speaking candidly in parliament upon his return from extended treatment abroad, the legislator recounted a perilous health ordeal that began at the prestigious Nairobi Hospital and culminated in a desperate airlift to Dubai.

His testimony, delivered with raw emotion, has ignited demands for immediate regulatory intervention, raising profound questions about access to safe healthcare for ordinary Kenyans.

It was approximately 15 months ago when Mr Kirwa first sought treatment at Nairobi Hospital for a serious, undisclosed condition. What followed, he alleges, was a cascade of ineffective medications that failed to alleviate his symptoms and instead precipitated a rapid deterioration. “I was to die in a week,” Mr Kirwa declared, his voice filled with emotion.

He described how the drugs prescribed by Kenyan physicians seemed to offer no relief, leaving him on the brink of collapse.

Only an emergency flight to Dubai, facilitated at considerable personal expense, averted what he now views as an avoidable tragedy. Upon arrival in the United Arab Emirates, the narrative took a revelatory turn. Dubai’s medical team, after halting the Kenyan-sourced medications, administered what Mr Kirwa described as “exactly the same medicine,” but in versions that proved miraculously effective.

“The doctors in Dubai said that most of the medication in Kenya has a problem,” he recounted, highlighting a discrepancy that points to potential substandard or counterfeit products infiltrating the supply chain.

His recovery in Dubai paved the way for further specialised care in the United States, from which he has now returned to Parliament, determined to amplify his experience into a clarion call for reform. Mr Kirwa’s account is not merely personal; it lays bare systemic frailties in Kenya’s pharmaceutical oversight.

Established under the Pharmacy and Poisons Act (Cap 244), the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) bears the solemn duty to evaluate, register, and authorise medicines, vaccines, and medical devices for the market. Yet, the MP’s allegations suggest a regulatory slumber that endangers lives. “I want to ask the government to look at the medicine we have in this country,” he implored, directing a pointed rebuke at the PPB for allegedly failing in its mandate.

Echoing this sentiment, online commentators have decried the board’s apparent inaction, with one observer noting, “If Nairobi Hospital cannot give you genuine drugs, woe unto you who relies on medication from your village dispensary.”

The implications extend far beyond the corridors of elite facilities like Nairobi Hospital. For the vast majority of Kenyans, those without the means for international evacuation, Mr Kirwa’s story evokes a chilling reality. Now, what about those who cannot afford an alternative? Where will they run to? In a nation where public health services strain under resource constraints, substandard drugs could silently claim countless victims, exacerbating inequalities in an already beleaguered system.

Public Health Cabinet Secretary, Hon. Aden Duale, has been urged to spearhead an immediate crackdown on health facilities, ensuring rigorous audits and enforcement to guarantee that only verified, effective medicines reach patients’ bedsides. Mr Kirwa’s plea has resonated widely on social media and in parliamentary circles, with calls mounting for lawmakers both in the National Assembly and the Senate to demand a formal statement from relevant authorities.

As President William Samoei Ruto’s administration grapples with broader economic pressures, this episode underscores the imperative of safeguarding public health as a cornerstone of national stability.

Industry estimates suggest that as much as 30% of medicines in the country may be fake, leading to treatment failures, prolonged illness, and death. While the official rate reported by the Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) is lower, industry associations estimate a much higher prevalence, sometimes up to 30%. The World Health Organization (WHO) warns that globally, one in ten medical products in low- and middle-income countries is substandard or falsified.

Falsified medicines for critical conditions like malaria, HIV/AIDS, and cancer are rampant and often contain incorrect or no active ingredients, or even harmful substances. This contributes to the rise of antimicrobial resistance and is linked to an estimated 100,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Anti-Counterfeit Authority (ACA) estimates Kenya loses at least KSh 15 billion annually to this illicit trade. Antibiotics, antimalarials, and high-value cancer drugs are among the most commonly counterfeited products.

[/full]