Kenya, too, has its own sobering examples. In 2018, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) flagged over 70% of state corporations for tribal imbalance in recruitment, with senior positions often dominated by individuals from the sitting President’s ethnic community. This systemic exclusion has fuelled resentment and eroded public trust in government appointments

To unlock the full article:

Choose one of the options below:

- Ksh 10 – This article only

- Ksh 300 – Monthly subscription

- Ksh 2340 – Yearly subscription (10% off)

The Weekly Vision Editorial Desk

Discrimination in the workplace, whether by race, caste, or tribe, is not merely an injustice to the individual; it is also a danger to society at large. When voices are dismissed because they come from those deemed “lesser,” institutions risk silencing truths that could protect the public from rot within.

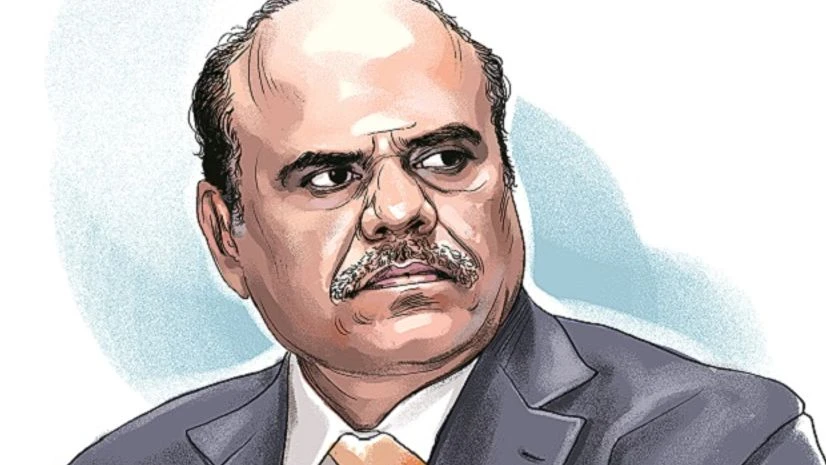

Take the case of Justice Chinnaswamy Swaminathan Karnan, the first Dalit judge of the Madras High Court. Dalits, historically branded “untouchable,” constitute nearly a sixth of India’s population, yet their representation in the higher judiciary remains negligible. Karnan’s career was marred not just by personal controversy but by the weight of systemic prejudice.

When he raised the alarm in 2017, writing to the Prime Minister to allege corruption among 20 judges, the establishment turned on him. Instead of investigating his claims, the Supreme Court branded him contemptuous, declared him unstable, and sent him to prison, an extraordinary fate for a sitting judge.

Years later, when sacks of black money were uncovered at the residence of Justice Yashwant Varma, the uncomfortable possibility arises that Karnan was not mad, nor merely bitter, but inconveniently correct. His warnings, stifled under the veil of contempt proceedings, echo with chilling clarity today.

This episode shows how discrimination blinds us. By dismissing Karnan, a Dalit outsider in an elite judicial club, India’s judiciary may have buried truths that should have been confronted head-on. Tribalism, racism, and caste prejudice are not only morally corrosive but institutionally reckless: they shield misconduct, silence dissent, and erode the credibility of public institutions.

Kenya, too, has its own sobering examples. In 2018, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) flagged over 70% of state corporations for tribal imbalance in recruitment, with senior positions often dominated by individuals from the sitting President’s ethnic community. This systemic exclusion has fuelled resentment and eroded public trust in government appointments.

Similarly, the 2007–2008 post-election violence revealed the deadly consequences of tribal favouritism in politics and employment. Communities perceived as “outsiders” in certain regions were uprooted, businesses destroyed, and thousands displaced simply because their tribe was viewed as politically incompatible. What began as an electoral dispute escalated into a tribal purge, underscoring how discrimination can quickly spiral into national tragedy.

In the private sector, racial prejudice has also left scars. For decades, Asian-Kenyans complained of being treated as perpetual foreigners, despite their deep roots in the country. Employment advertisements in the 1990s and early 2000s openly excluded them from managerial roles in public service, branding them “non-indigenous.” It took years of legal and constitutional reforms to begin addressing these inequities, yet informal barriers and stereotypes persist even today.

Justice Karnan’s story, therefore, is not simply one of personal tragedy but of systemic failure. And Kenya’s own history shows that tribal and racial bias, when entrenched, not only humiliates individuals but also prevents institutions from functioning fairly. It is a stark reminder that when we allow prejudice to dictate whose voice counts, we may also allow corruption, violence, and exclusion to flourish.

The question now is whether our institutions can rise above these biases to reform from within, or whether history will repeat itself until the cost becomes unbearable.

[/full]