By The Weekly Vision Investigations Desk

The creation of Kenya’s Social Health Authority (SHA) in October 2024 was meant to turn the page on the scandal-plagued National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF). However, instead of reform, revelations of fraudulent payments to non-existent hospitals have raised doubts about whether SHA is deepening the systemic corruption it was supposed to solve, rather than delivering universal health coverage.

Investigations by the Rural and Urban Private Hospitals Association (RUPHA) unearthed shocking details of “ghost hospitals” siphoning public funds. One such entity, Trenya Hospital Limited, received more than KSh 10 million despite having no staff, patients, or infrastructure. RUPHA described it as a “hospital in a phone,” existing only on paper but listed as a licensed facility in SHA’s records.

Another glaring case is the Nyandiwa Dispensary in Homa Bay County, which was abandoned nearly a decade ago but nonetheless received a credit of KSh 19.9 million. Locals confirmed no services have been offered there for years, yet SHA classified it as a Level 4 hospital. SHA Chief Executive Dr Mercy Mwangangi defended the payments, insisting they were directed to an upgraded Nyandiwa Level 4 Hospital that had retained the old dispensary’s bank account. However, Homa Bay’s Director of Public Health, Amos Dullo, attributed the anomaly to SHA’s flawed system, deepening the controversy.

The scandal has also exposed possible conflicts of interest. Ladnan Hospital, linked to SHA Chairman Dr Abdi Mohamed Abdi, pocketed KSh 28 million for what whistleblowers describe as minimal services. In another case, KSh 54.3 million earmarked for Kandiege Sub-County Hospital saw only KSh 14 million reach patient care, with KSh 40 million unaccounted for.

These revelations echo NHIF’s notorious “ghost patient” scams, suggesting SHA has not only replicated past loopholes but also entrenched political patronage.

While dubious facilities pocket millions, genuine hospitals are being starved of resources. RUPHA disclosed that 95% of claims from private hospitals are routinely rejected without explanation. St Mary’s Hospital, for instance, is burdened with KSh 180 million in unpaid arrears, forcing it to shut down services.

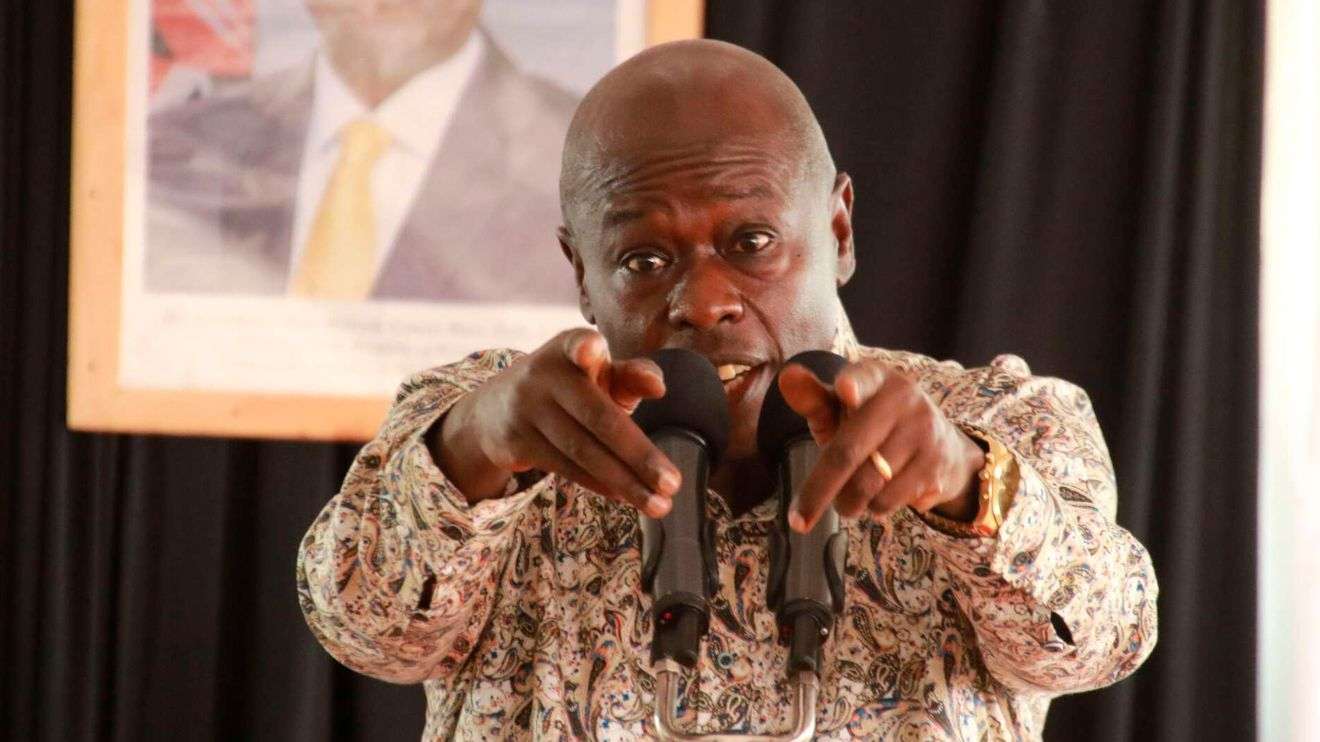

Oversight has also faltered. A High Court ruling recently nullified Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale’s verification committee, terming it unconstitutional. Despite this, SHA continues to make selective payments, often favouring hospitals with political connections. RUPHA’s chairperson, Brian Lishenga, accused the authority of degenerating into a “political machine” rather than a healthcare financier.

The Ministry of Health’s KSh 104 billion digitalisation programme, touted as a safeguard against fraud, has been dismissed by RUPHA as “smoke and mirrors,” incapable of flagging ghost facilities.

On 8 August 2025, SHA suspended 40 hospitals for fraud. Yet with biometric verification systems still underdeveloped, confidence in the new authority remains low. Critics argue that the public’s hopes for universal health coverage are being dashed as corruption and mismanagement compromise service delivery.

These events highlight a troubling reality: instead of restoring integrity to health financing, SHA is enabling large-scale graft. With public outrage mounting, urgent reforms are needed if billions earmarked for healthcare are to reach real patients instead of vanishing into ghost hospitals.