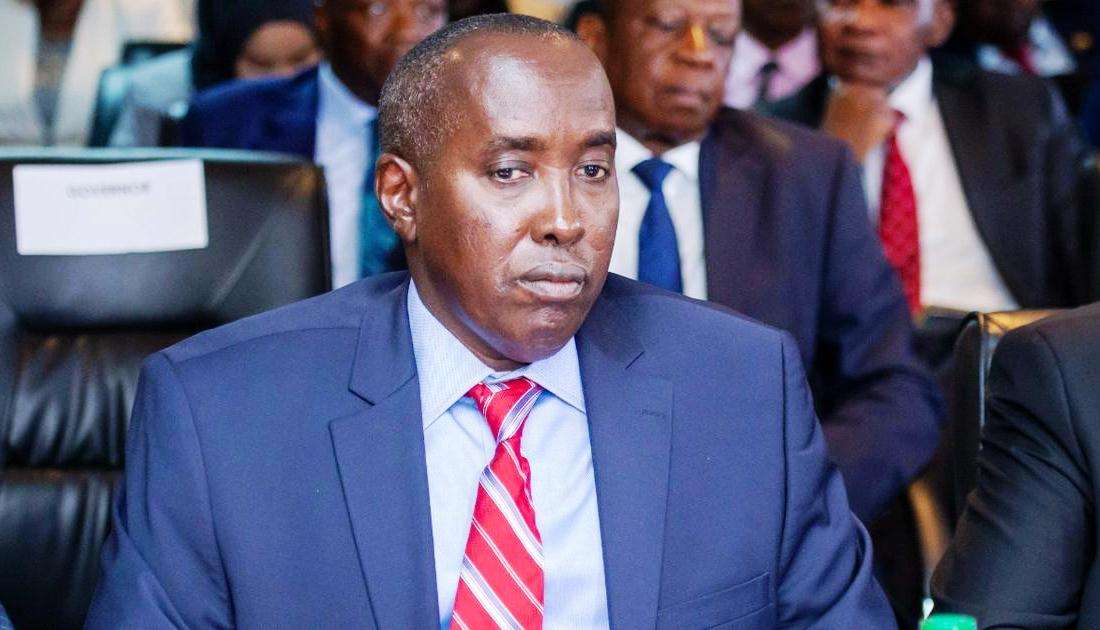

David Mategwa, chairman of the scandal-laden Police SACCO, emerged as KUSCCO’s interim chairperson, while Matthew Ruto of Kericho’s Imarisha SACCO, linked to a questionable Ksh 3 million retirement payout—also secured a seat on the interim board. Mategwa faces allegations of obstructing Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) probes and bribing Sacco Societies Regulatory Authority (SASRA) officials to suppress evidence of fraud at Police SACCO, accusations he denies, though doubts persist regarding his qualifications

By Mdadisi Mmoja

Kenya’s cooperative sector, a lifeline for millions, faces potential collapse unless urgent measures address a devastating scandal. Central to this crisis is the Kenya Union of Savings and Credit Co-operatives (KUSCCO), once a trusted foundation for over 4,000 SACCOs, now ensnared in a financial debacle that has wiped out Ksh 12.5 billion between 2013 and 2024. As forensic audits reveal a web of deception, lawsuits intensify, and trust disintegrates, a pressing question confronts the nation’s 6.4 million SACCO members: How did a system designed to safeguard their savings unravel so catastrophically?

Founded in 1973, KUSCCO was designed to bolster Kenya’s SACCOs, pooling resources to provide loans, insurance, and financial stability for teachers, police officers, and ordinary workers. Yet, beneath this façade of dependability, a crisis is brewing. A forensic audit by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), submitted to national security agencies in February 2025, revealed a Ksh 12.5 billion deficit driven by unauthorised withdrawals, inflated profits, and gross mismanagement. Non-performing loans consumed Ksh 3.7 billion, irregular commissions drained Ksh 2.7 billion, and a central finance fund lost Ksh 1.3 billion. Most alarmingly, financial statements were overstated by Ksh 9.3 billion, with some records bearing the forged signatures of auditor Alfred Basweti—reportedly deceased, though some sources claim he remains alive—his name was used to conceal fraud in 2022.

The scandal’s key figures stand exposed. George Ototo, KUSCCO’s Managing Director until his dismissal by the Ministry of Cooperatives in January 2024, oversaw this financial unravelling. Alongside Finance Manager George Owino and former Chairman George Magutu, Ototo allegedly orchestrated a scheme involving cash diversions—such as Ksh 206 million withdrawn in sacks—under dubious pretexts. Following Ototo’s exit, the entire board was dissolved, yet the saga took an unexpected turn. David Mategwa, Chairman of the controversy-laden Police SACCO, emerged as KUSCCO’s interim Chairperson, while Matthew Ruto of Kericho’s Imarisha SACCO, linked to a questionable Ksh 3 million retirement payout, also secured a seat on the interim board.

Mategwa faces allegations of obstructing Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) probes and bribing Sacco Societies Regulatory Authority (SASRA) officials to suppress evidence of fraud at Police SACCO—accusations he refutes, though doubts linger over his qualifications. Ruto’s tenure at Imarisha SACCO, already marred by financial irregularities, raises parallel concerns. Why, then, do these men remain in positions of influence? Both served under Ototo’s scandal-plagued regime, yet their reappointment to the interim board in early 2025 suggests either a lack of alternatives or a tolerance for tainted leadership. Analysts question whether their presence undermines the recovery effort, with one financial expert noting, “Retaining figures tied to past failures risks perpetuating the very culture that almost sank KUSCCO.”

The consequences have devastated member SACCOs. Nyati Sacco Society, with Ksh 90 million trapped in KUSCCO, has launched legal action against SASRA, challenging a directive that compels affiliates to absorb the losses—a policy it deems “grossly unjust.” Larger SACCOs, such as Mhasibu (Ksh 480 million at risk) and Kimisitu (Ksh 353 million), are cutting dividends and tightening lending, leaving members in financial limbo. For savers, the stakes are personal. “This isn’t just money,” one member lamented. “It’s our dreams, stolen.”

How did KUSCCO evade scrutiny for so long? The answer lies in a regulatory gap. Operating between SASRA, the Ministry of Cooperatives, and the Commissioner for Cooperatives, KUSCCO exploited weak oversight. Unlike banks, SACCOs lack deposit insurance or a lender of last resort, rendering them vulnerable. Cabinet Secretary Wycliffe Oparanya conceded that the Sacco Societies Act of 2008 failed to curb an apex body that expanded into deposit-taking and insurance without proper authorisation. SASRA’s response, deferring losses over years, contravenes international accounting standards, sparking a dispute with the Institute of Certified Public Accountants of Kenya (ICPAK). To SACCOs like Nyati, this feels less like a rescue and more like a shield for KUSCCO’s misdeeds.

KUSCCO currently operates under an interim board led by Mategwa, tasked with recovering Ksh 8.8 billion within three years. The strategy includes reducing staff from 243 to 96, selling assets like KUSCCO Housing, and pursuing legal action against Ototo and seven others, who were charged in February but released on bail. The Cooperative Bill 2024, recently enacted, pledges stricter governance, yet KUSCCO’s Ksh 17.7 billion in liabilities far exceeds its Ksh 5.2 billion in assets. PwC warns that recovery could take decades if it happens at all, a sobering prospect for savers awaiting restitution.

The KUSCCO scandal serves as a stark warning: without robust accountability, even the most revered institutions can falter. The lingering presence of Mategwa and Ruto on the interim board only deepens the unease. Were they reinstated due to their experience, or does their return signal a failure to break from a compromised past? As Kenya’s cooperative sector peers into an uncertain future, the pursuit of justice, and the restoration of trust, remains elusive. For now, millions of savers can only watch and wait, hoping their stolen dreams might one day be reclaimed.